sociology, cities, psychogeography, soundscapes, sound pavilion

RESEARCH // SPECULATE

‘Let everyone look at the space around them. What do they see? Do they see time? They live time, after all; they are in time. Yet all anyone sees is movements. In nature, time is apprehended within space, in the very heart of space: the hour of the day, the season, the elevation of the sun above the horizon…With the advent of modernity time has vanished from social space’ (Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, 2000, p. 95)

We cannot understand the idea of a city without involving temporal actions in it. In his book, The Production of Space, Lefebvre found that in the modern city there was a lack of temporal references. Lefebvre defended time as being essential for the lived experience and attempted to incorporate a social dimension in the creation of space. Arguably site-specific sound installations represent one of the few current attempts in which a connection between urban construction and city life has been proposed in a more participatory way.

Sound interventions in urban space manage to establish a close and very natural dialogue with individuals and the city, due to the temporal factor of all three (sounds, individuals and cities) share, they make us become more aware of time passing in our cities. The momentary passing of sounds raises our awards of time passing in our cities, as well as in our own lives. But can these temporary installations be upscaled and employed in larger-scale, more permanent architecture?

Cities like Hong Kong and London where we are based, are high speed, visually rich urban environments: glittering skylines, vibrant markets, colourful buildings in a hyper dense cityscape: cities in motion. But, when you close your eyes and think of the city, what do you hear? Do you hear time? These cities are truly three dimensional with a multitude of diverse noises, above, below and around us. There is an unseen rich cacophony, a steady heartbeat of soundscapes: the sloshing of water, the slow and steady grumble of passing boats, the melodic birdsong in the parks and the play of multi lingual mutterings. These cities are in a constant state of audible flux and intonation. As urban environments densify and grow, so does their acoustic space. It also becomes more compressed, and in doing so changes our aural perception, making it often difficult to orientate oneself within the city. Sound is often an undervalued and overseen constraint by architects. When it is accounted for, the design is usually intended to buffer it or insulate it out.

Alternatively, it can be used to reconnect disparate parts of the city; temporally, spatially, socially and historically. Sound in the city can be used as a channel for spatial recognition of people through the simple act of listening. As a tool, it can be focused on the restoration and improvement of public spaces. Listening gives spatial awareness; the sonic world of the city must be designed for, constructed and reconstructed.

Spaces are produced socially, meaning that social relations in time and space can be considered usefully as rhythms. Can architecture in public spaces use and augment sound to establish a close and very natural dialogue with individuals and the city? We are becoming more and more a visually-obsessed society blessed with a dazzling array of gadgets and tools to help us explore and understand places in the digital realm, often before we explore it physically. We record and consume imagery at light speed - representations of place often replacing real sensorial experiences. Therein lies a paradox between being more connected to our world whilst becoming equally detracted from it in a physical sense.

Our concept is thus a simple one. It is about place, and what it feels like to be in the city. It is an architecture designed only to be fully understood and experienced by those present. Through a more acute awareness of acoustic interactions with the city, carefully designed soundscapes can help develop a notion of the democratisation of space. Sound specific installations augment hearing to a more perceptible state, creating a space of immersion for people to contemplate their relationship with their everyday common spaces, in a more intimate capacity

These observations formed our initial point of departure for the design of our sound pavilion ‘Mirrored Unseen’. This architecture is designed to point out the simultaneity of actions in the city, and therefore the confluence of different experiences of the people that make it up. We draw influences from artists such as Maryanne Amacher and Llorenç Barber, whose work on sound pointed to urban ideas of psychogeography and the study of the city through the effects of its configuration over the emotions and affective behaviour of its citizens. Amacher’s project, City Links: Buffalo, was a 28-hour sound piece where multiple microphones were placed in different parts of the city. All the information recorded was broadcasted live on the radio and thereby establishing an acoustic connection those areas of space and time that one would consider to be in different states across the city.

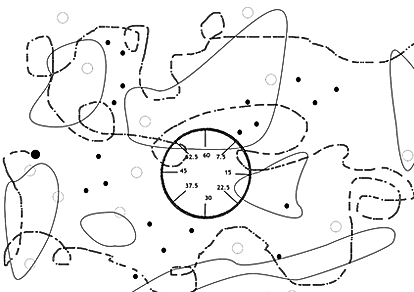

Our urban intervention, ‘Mirrored Unseen’ invites the visitor to explore space through sound. The sounds observed are in essence an event of temporal development. Each visitor is invited to explore the different layers of sound and map this unseen space as they navigate around the pavilion and experience the passing of time. Forming a macro to micro experience of this distinct location, each mirror is different - specifically designed, tuned and orientated to distill and unravel the textures and tones of unseen spaces around us.

The forms and arrangement of the mirrors guide visitors to become more aware of their context and to create a very personal relationship with the space and all the activities in it. The mirrors also invite performers as well as the public to use the pavilion: occupying them as bandstands for performances, auditoria for readings, screens for projections and backdrops for artistic experimentation. It explores the impact these soundscapes produce not only on the physical city but also on the role that people play in it, to establish a dialogue with all of the dynamics of a particular space.